Microeconomics for Lawyers

| What area(s) of law does this episode consider? | Applied microeconomics for lawyers. Dr Beaton’s episode is perhaps one of the most widely applicable topics that will appeal to all lawyers regardless of practice size or type. He discusses microeconomics in the legal services industry, particularly in the context of marketing, business strategy and differentiation. |

| Why is this topic relevant? | Microeconomics is a branch of economics that studies the behaviour of firms and individuals in making decisions about the allocation of resources. There is no doubt that the legal services industry is changing. The way in which legal services are delivered – and billed – has changed dramatically over the past two decades, and even more recently throughout COVID-19. The digitalisation of legal services, dispute resolution platforms and flexible fee structures are only some examples of this. |

| Some examples Dr Beaton discusses

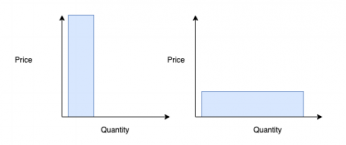

| Advertising by lawyers: Dr Beaton starts by briefly mentioning the US case of Bates v State Bar of Arizona 433 U.S 350 (1977). Bates started to advertise the firm’s services. The question for the Court was whether the Arizona rule, which restricted legal advertising, violated the freedom of speech of Bates and his firm as guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth amendments. The Court held that it did; ultimately finding that allowing attorneys to advertise would not harm the legal profession or the administration of justice. Prior to this case, it was not considered proper (or in fact legal) for lawyers to advertise their services. Substitution: is a key concept when considering the law of supply and demand. A substitute is a product or service that can easily be replaced with another. Substitutes provide additional choices and alternatives for consumers while also creating competition. Dr Beaton considers substitution in legal services, being not only the substitution of other lawyers, but generic substitutes in the form of technology, such as document automation platforms. As more substitutes enter the market supply increases and demand remains constant which results in a decline in the price of legal services. This is proven by Dr Beaton’s example of purchasing a ‘Non-interest bearing loan’ template from an online platform for $35. Commoditisation: of legal services refers to a situation where the client believes that most law firms and most lawyers can perform the same task equally well. Put another way, the client views the work product as a commodity, meaning that clients care less about who they are obtaining services from and more about the price of the service. This results in a downward pressure on price. Pricing models: Essentially there are two types of pricing which are diametrically opposed: input based pricing (i.e. charging based on the number of hours worked) and outcomes based pricing (charging a fixed amount for a specific outcome). The traditional form of pricing is input based pricing based on hourly rates. US law firm consultant, Altman Weil studied the profitability of matters, comparing those that used hourly rates against those that used fixed rates, finding that those that used fixed rates were more profitable. Both low pricing and high pricing are valid business models. Consider the following diagram:

The graph on the left represents a ‘premium’ product, which attracts a few highly valuable clients; the graph on the right represents a ‘high volume’ product, where a large number of clients are charged lower fees. But both blue rectangles have the same area – each strategy is equally valid. Does your practice sell a ‘premium’ product, or a ‘high volume’ product? Incentives: Charging based on hourly rates can create a perverse incentive because time-charging promotes inefficiency, the longer it takes to do the task the more the client is charged. Measurement: ‘If it’s not measured it can’t be managed’ – It’s imperative that information is measured and contextualised. A balanced scorecard will measure money, clients, talent and innovation money and innovation. If charging and analysing fixed fees you need to consider cash flow, debtor days and gross margin; financial measures help you assess profit. Both client and employee satisfaction should be measured and innovation that focuses on improvements should be considered. Unmet legal demand: A study completed by the Solicitors Regulation Authority in England and Wales found that only 15% of legal needs are being met by solicitors, of the remaining 85%, around 50% are recognised as unaddressed and the 25% remainder is being fulfilled by accountants, or family and friends. This highlights that there is a vast latent market for solicitors. |

| What are the practical takeaways? |

|

You must be a subscriber to access this content.

You must be a subscriber to access this content.